Act One and Two are set in medieval and industrial England. In both, the English are an essentially good people, but a malevolent "Dragon" rules them, ruining their lives - until St. George kills it and frees the people to be happy. Act Three is set in contemporary Britain, where the "Dragon" is now, for some reason, "within" all people, and cannot be slain, so the people decide to live as they are, and reject St. George. The reason for this difference is vaguely explained as being because "people have changed" by Act Three.

How can this narrative, overall, be interpreted? The only message I am able to untangle is this: it was possible in the past to remove problems, but in contemporary Britain it is not. We just have to live with them.

Mullarkey is not saying that the problems were never removed in Act One and Two - because they were removed, by both slayings of the dragon: these led to temporary utopias. Also, it is not the case that all of Act One and Two were illusory: their events are remembered and referred to by several characters in Act Three. So the people of England really were freed from their external problems in previous eras, but no longer can be - because of something about how those problems are now internalised.

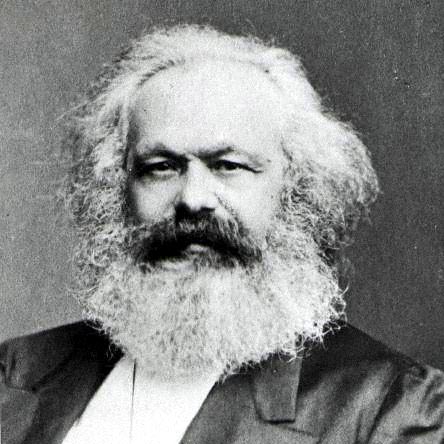

This means Mullarkey, like Marx before him, is attempting to develop an overarching narrative of history's progress, and pinpoint landmarks within it. Good idea, Mullarkey! That never goes wrong.

No-one who has ever come up with a plan for history's progression has ever ended up getting it wrong - not Marx, not Hegel, not the Whigs, definitely not Fukuyama!

And, whereas Marx has communist utopia at the end of his historical progression, Mullarkey has - for some reason - a society in which, uniquely within human history, evil can no longer be expunged - evil is more insidious. And that society, that Fukuyaman end-of-history, just so happens to be the present day. His evidence for evil's ascendancy in recent years is, I think, mainly the increase in binge drinking and video games - and I'm not even joking.

So Mullarkey genuinely believes there's something unique about 21st century society which makes it harder to get rid of evil. Wow. A historical understanding that is Fukuyamanally shit.

No comments:

Post a Comment